A Sermon related to the Parable of the Talents (Matthew 25: 14 – 30) – Patricia Billsborrow – Pickmere 19th November 2023

Last Sunday, rather than go to a local church service as I was not on the Plan, I went to have a time of peace and reflection at the Friends Meeting House at Fradely. It was something one of my church members in Birkenhead did every Remembrance Sunday and it was for her and for me a time of quiet where I could share silence with others, remembering and also praying for God’s presence in a search for peace. As I went in, with a friend from Davenham I was handed this little card which speaks of what the Quakers say: ‘There is something sacred in all people, all people are equal before God, Religion is about the whole of life, Each person is unique a precious child of God’.

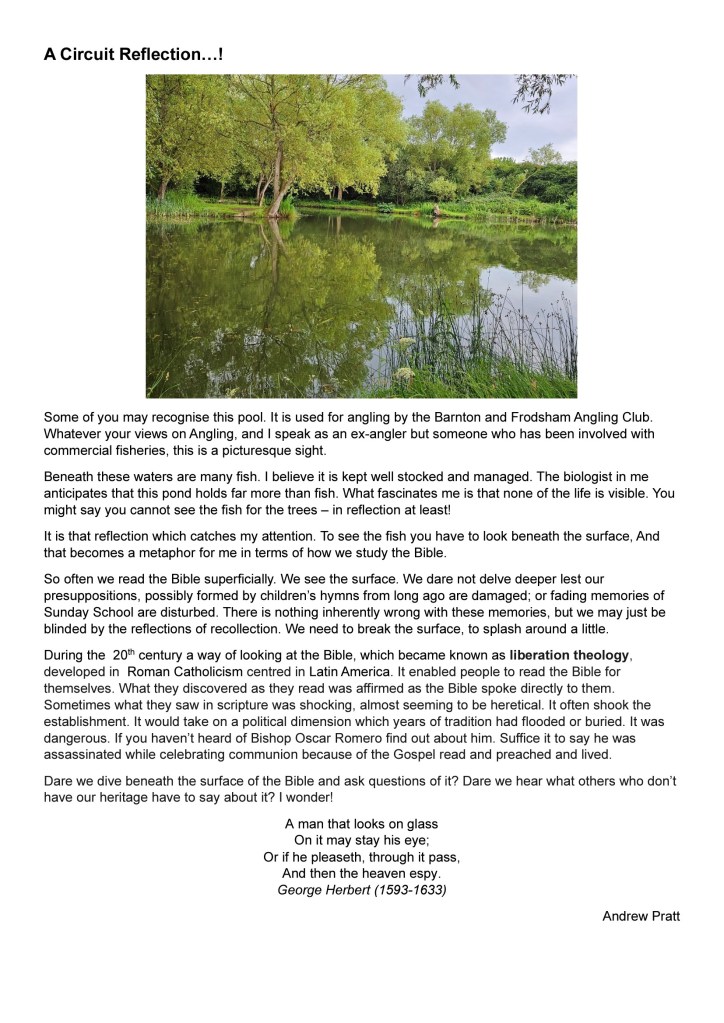

As I sat in the quiet space I was facing a window which had a lovely tree outside still fully leaved with beautiful autumn colours………….I noticed something I don’t think I have ever noticed before that every leave was different, the colours, the shapes the twists and turns were all unique and yet all of those leaves were attached to the one tree, they would soon be beginning to fall but behind them would be the buds of new life………………..an image which made me think of those words I had just read, but also my own belief in the words from Scripture that all of us are made in God’s image whoever we are, and are all attached to the “one tree” so to speak and how important it is to endeavour to pray for God’s guidance as we all travel the same journey whatever colour we are, whatever language we speak, however we recognise God and all of us must seek to become the world that was envisaged at the time of Creation……………………….it was quite a lesson, I then came home and read the Gospel set for today about the talents. I don’t think we every really go into the parables seeking to look more deeply into the words but it is perhaps important to seek what those talents actually were……………according to the foot of the page in my Bible the note says that it was more than 15 years of wages for a labourer……………….an awful lot of money which was given for the workers to care for on his behalf, and I am sure many of us would sympathise with the man who buried it so that it did not lose value rather than get caught up in more risky endeavours………………however Matthew was not meaning the people listening, or indeed we in our own time to think of it in those terms, but in the terms of the many gifts we are given by the God who comes to us in the person of Jesus willing to give so much even to go to the cross for the salvation of the people………………..and how we are to react to the gifts that we ourselves have and how we should use them in accordance with the Gospel of Love………….of God, quite easy…………..of our neighbours…………………….how do we do that……………well as we ourselves would want to be loved (cared for). There is of course a temptation to feel comfortable in the faith community into which we have either been born or have come to know having met Jesus and heard him say to us, follow me, and therefore, and to some extent that has become more tempting since the pandemic, to close ourselves away within the community where we feel comfortable rather than share the gifts which come through faith with the wider community, those who have needs sometimes physical through things like the food bank and homelessness projects, those who are lonely and lost in the wider world, those who are afraid, I could site many other examples, and yet the parable is saying that is not what the Owner of the vineyard is asking them to do, he is asking his workers to use the very generous gifts he has given them to create growth and to develop the work he has entrusted to them. In more everyday terms that we, who have heard those words and heard Jesus call to us through his life and witness of which we read in the Gospels, should use the love we have for our creator to make a difference through our interaction not just with the familiar but with those people whose lives are very different from ours, whose journey has been very different from ours, to make them feel part of the world wide family, the kingdom of God, which was envisaged when God created the world, the one world, the multicoloured and experienced world, we are living in today. When I looked at that tree, and those amazing coloured leaves and reflected on them, I saw beyond the natural beauty to the world as it is today, and that whichever journey we find ourselves on, we should be aware of the journies of others and seek to build a world where instead of suspicion and hatred there is kinship and peace so that we might play our part in building that world which was intended at the beginning. All of us whoever we are of different understandings of faith, of different nationalities and understanding are on the same journey with the same end in view. Let us play our part in building that wonderful vineyard where all participants have value and are part of the one family one of the many leaves, attached to the same tree and be thankful. Amen

© Rev Patricia Billsborrow, reproduced here with permission